6.1 THROUGH WHAT AVENUES IS CONTENT REPORTED?

As with any complaints adjudication process, the designers of the system must consider who has standing to bring a complaint for consideration. Should anyone have the ability to flag a piece of content for review by the EMB? Only political parties and candidates? Should the EMB aggregate complaints received by other government agencies or bodies?

The South African system allows that “the  Commission shall receive complaints of disinformation during the election period from any person.”1 This is operationalized through the Real411 system, which includes a web portal where any member of the public, regardless of whether they are eligible voters, can flag content for review. The portal now receives complaints year-round, not only during the electoral period, and is maintained by the civil society group Media Monitoring Africa, which organizes the three-person review teams of outside experts that make up the Digital Disinformation Commission (DDC). During elections, the DDC makes recommendations to the IEC’s Directorate of Electoral Offenses on actions to be considered.

Commission shall receive complaints of disinformation during the election period from any person.”1 This is operationalized through the Real411 system, which includes a web portal where any member of the public, regardless of whether they are eligible voters, can flag content for review. The portal now receives complaints year-round, not only during the electoral period, and is maintained by the civil society group Media Monitoring Africa, which organizes the three-person review teams of outside experts that make up the Digital Disinformation Commission (DDC). During elections, the DDC makes recommendations to the IEC’s Directorate of Electoral Offenses on actions to be considered.

Systems that are open to public reporting from any member of the public provide opportunities for brigading, in which actors wishing to overwhelm or discredit the system could flood the reporting channel with disingenuous or inaccurate reports. A non-disinformation example of this took place ahead of 2020 Serbian elections. In this instance, a party that was boycotting the elections created a viral Facebook campaign encouraging supporters to submit claims via the EMB’s election complaints process for the suspected purpose of overwhelming the EMB’s dispute resolution capacity. Though the cases were dismissed, they reportedly caused administrative delays which weighed on the effectiveness of the complaints process. South Africa attempts to mitigate against this risk by requiring complainants to confidentially submit their names and email addresses along with their complaint.

Bawaslu, recognizing the ways in which overly formal reporting mechanisms can significantly slow collaboration, maintained informal communication channels with counterparts at the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology, the police, and the army via WhatsApp to refer and share intelligence about complaints in addition to receiving complaints directly from the public. On a weekly basis, the Ministry of Communication and Information Technology would collect and send the reports of content they had collected to Bawaslu for review, classification and a determination on further action. Interlocutors at Bawaslu estimate that they received an average of 300 to 400 reports per week.

6.2 WHAT ARE THE STANDARDS TO DETERMINE VIOLATING CONTENT

The definitions that a disinformation complaints referral and adjudication body uses to determine what content constitutes a violation that requires remedy or redress must be clearly and narrowly drawn and fit within the country’s constitutional, legal and regulatory framework.

In South Africa, the complaints process is integrated into the draft Code of Conduct for Measure to Address Disinformation Intended to Cause Harm During the Election Period. The code itself draws clear definitions of what constitutes disinformation – specifically, intent to cause public harm, which includes disrupting or preventing elections or influencing the conduct or outcome of an election. As discussed in the subsection on codes of conduct, the code's definitions are firmly grounded in the South African Constitution and electoral legal framework. The same standards are used in each phase of the complaints process, by the DDC, which is external to the IEC, as well as by the Electoral Offenses Office and the Commissioners within the IEC.

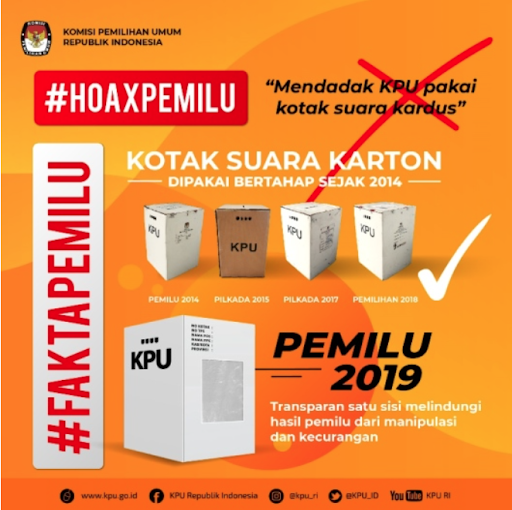

Arriving at standardized definitions presents an opportunity for EMBs to engage in consultation and relationship building with potential allies in the fight against electoral disinformation. In Indonesia, Bawaslu created standardized definitions for unlawful content in electoral campaigns. Prior to 2018 local elections, existing laws outlined categories of prohibited content, such as hate speech, slander, and hoaxes, but these categories lacked clear definitions. To arrive at definitions, IFES supported Bawaslu in conducting a series of roundtable discussions engaging more than 40 stakeholders from government, civil society and religious organizations to discuss definitions for the types of content prohibited in electoral campaigns. This feedback was then taken into consideration in the formulation of Bawaslu’s Regulation on Prohibited Electoral Campaign Content.2 Consultation can be more narrowly drawn as well; in the run up to the launch of their complaints process, definitions in South Africa were discussed by a working group that included IEC members, media lawyers and members of the press.

Definitions are also likely to evolve over time as the complaints process is put to the test. In South Africa, initial discussions included whether hate speech and attacks on journalists should be covered by the complaints process. Though both were excluded from the definitions used during 2019 elections, Media Monitoring Africa and their partners developed definitions and reporting processes for these additional categories of complaints after the elections. Complaints on these additional topics are now able to be submitted via the complaints portal, and may be considered by the IEC for future elections.

It might also be useful to examine existing legal and regulatory frameworks around gender-based violence, violence against women, or gender equality that can be used to create definitions for online content that may violate these laws and regulations. Including definitions specific to violations that disproportionately affect women and other marginalized groups is key in making sure their concerns and experiences are addressed through this effort.

6.3 REMEDIES, SANCTIONS, AND ENFORCEMENT OF DECISIONS

An adjudication process should provide for a variety of remedies and sanctions that can be adapted to fit the violation that is identified. It may be desirable for a complaints adjudication process to have more remedies at its disposal than the referral of content to the platforms for removal.

In both South Africa and Indonesia, the most common judgement regarding the referred complaints was to take no action - either because the content was not deemed to rise to the threshold of constituting public harm or because the content fell outside of the narrow focus on election-related content and therefore was outside the jurisdiction of the EMB.

The South African IEC has discretion to determine appropriate avenues for recourse. These include:3

- Determining that no action is necessary

- Engagement with the party or candidate that has committed the violation to urge compliance with the disinformation code of conduct, which stipulates that signatories must act to correct disinformation and remedy public harm in consultation with the IEC, including disinformation that originates with the signatories’ representatives and supporters.

- Referral to the appropriate regulatory or industry body that has jurisdiction, including the Press Council of South Africa or the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa

- Referral to a relevant public body, such as the police, for further investigation or action

- Referral to the Electoral Court for appropriate penalty or sanction

- Use of IEC communication channels to correct disinformation and remedy public harm

The remedies envisioned through Bawaslu’s process were narrower than those of their South African counterparts. Bawaslu had authority to observe social media during the campaign period, but not to take action against violators. The primary focus of their process was to elevate content for review and removal by the platforms. In instances where content was in violation of platform community standards, the content was removed or its distribution limited in accordance with platform policies. For Facebook, in instances where content was in violation of Indonesian law but did not violate Facebook’s community standards, content was ‘geoblocked’ – meaning that the post was inaccessible from within Indonesia, but was still accessible outside of the country.

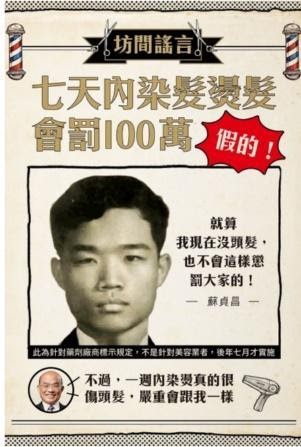

In addition to content removal or restriction, Bawaslu also used the content they collected to identify voter education and voter information themes to emphasize in their public messaging. They also referred cases to the criminal court system in instances where content violated the criminal code. Bawaslu reported that there were no instances of sanctions against political parties using the criminal code, though actions were taken against individuals. Notably, the highly-publicized “seven containers hoax” which alleged that cargo ships full of pre-voted ballots had been sent to Jakarta, led to criminal charges against the individuals that started and spread the hoax.

6.4 HOW WILL THE SYSTEM ACT EXPEDITIOUSLY?

The possible timeline for adjudication and action is a significant challenge for complaints referral and adjudication processes. Though some content identified as high priority was expeditiously addressed, the systems that Indonesia and South Africa developed and used during their respective elections had multiple stages that at times took weeks to clear in order to issue a decision on an individual piece of content. Given the volume of posts, quick iteration of messages and tactics, and the speed with which problematic content can go viral, a slow process for removing individual pieces of content is unlikely to have a measurable impact on the integrity of the information environment. By the time a piece of content has been in circulation for a day or two – much less a week or two – it is likely to have done the majority of its damage, and the churn of content will ensure that new narratives will have emerged to occupy public attention.

In instances where the remedy or sanction sought goes beyond content removal, as in the case of South Africa, a slower timeline may not reduce the effectiveness of the remedy. Media Monitoring Africa would at times pursue a dual track in which content would be referred to the IEC and to the platforms simultaneously: to the IEC for consideration of the array of remedies under their power to issue, and to the platforms for review of the content for expeditious removal. However, if the primary remedy sought by a complaints adjudication process is the removal of content from a social media platform, a multi-step complaints referral process may not be an efficient way to achieve it. Content removal may not be a goal that EMBs should be involved in at all.

6.5 HOW IS PUBLIC OUTREACH/PUBLIC AWARENESS RAISING BEING DONE?

The goals of a complaints referral and adjudication process should be twofold; the intent of such a system is to both remedy the harms of disinformation, as well as to build confidence among the electorate that authorities are effectively addressing the challenges of disinformation in ways that protect the integrity of the electoral process. Thinking through a communication strategy to publicize the efforts and successes of the process is a critical component to making the most of a complaints system. The very existence of the complaints system, if compellingly communicated to the public, can help to rebuild public perception of the trustworthiness of democratic processes and election results.

In the case of South Africa, a subsidiary benefit of running the complaints process was that the IEC could offer reassurances to the public after the election that the integrity of the election had not been undermined by coordinated malign actors seeking to distort outcomes or disrupt election processes. The referral mechanism in some ways also served as a crowdsourced media monitoring effort, and contributed to the conclusion that there was no evidence of foreign or state-linked influence operations that were operating at scale. The IEC concluded that there were instances of misinformation and disinformation, but no evidence of a coordinated disinformation campaign.

The complaints process developed by the IEC included planning for how to keep the public informed about the decisions that were made. As a way to build public awareness and interest in the complaints system, the IEC provided regular reports to the media that summarized the complaints that were received and how they were handled. Though the complaints process was only active for a brief period before elections, the IEC’s communication efforts helped build support for the complaints process, leading to calls for the system to continue even after the election.

6.6 Provide adequate time to develop and review the complaints process

An effective complaints adjudication process is a complex endeavor to start and to gain institutional buy-in. Such a system may take time for implementers to learn to use. The ramp-up time for a system may be extensive, particularly if it involves consultative elements and involves developing common definitions. Any existing system should be reviewed in advance of each election to ensure it is suited to the evolving threat of electoral disinformation.

Plans and consultations for South Africa’s Real411 System began in the fall of 2018 and the system was only able to begin operation in April 2019 ahead of May elections. Consultations on definitions of violating content in Indonesia, though at the time unconnected with the complaints referral system, took place a year in advance of 2019 elections.

The INEC of Nigeria deploys its longstanding

The INEC of Nigeria deploys its longstanding

Commission shall receive complaints of disinformation during the election period from

Commission shall receive complaints of disinformation during the election period from  7.1 Work to help EMBs to enhance dissemination of credible information

7.1 Work to help EMBs to enhance dissemination of credible information